| |

| |

|

|

Chicos de Varsovia (“Warsaw’s

Children”)

Inspiration for the book title came

from the 1944 Insurgents’s song: “Warsaw’s Children” - ("Warszawskie

Dzieci" - see below)

Ana Wajszczuk

“Warszawskie Dzieci …” - 1944

Warsaw Uprising song

https://pl.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warszawskie_dzieci

Refrain:

„Warszawskie dzieci,

pójdziemy w bój,

Za każdy kamień Twój, Stolico, damy krew!

Warszawskie dzieci, pójdziemy w bój,

Gdy padnie rozkaz Twój, poniesiem wrogom gniew!”

choir:

Warsaw's children, we go into

battle,

For every your stone , Capital, we'll give our blood!

Warsaw's children, we go into battle,

When you give your order, the wrath of enemies!

Text: Stanisław Ryszard Dobrowolski,

music: Andrzej Panufnik; composed - July 4, 1944, recorded August

1,1944 for the radio station Błyskawica, first broadcast – August 8,

1944;

http://www.tekstowo.pl/piosenka,zolnierska,warszawskie_dzieci.html

A Concept (”Myth”) of the

“People/Children of Warsaw”

From the book: THE JEWS IN THE LITERARY LEGEND OF THE JANUARY

UPRISING OF 1863. A CASE STUDY IN JEWISH STEREOTYPES IN POLISH

LITERATURE by Magdalena M. Opalski -

https://ruor.uottawa.ca/handle/10393/21177

Cyprian K. Norwid – 1861,

while abroad, responding to the news from WARSAW about unrest and

patriotic demonstrations, which followed a “miraculous apparition” –

prior to the 1863 National Uprising against the Russians:

/You ask:

what do I say when a Warsaw’s (little) child

rises backed-up by (in response to) a miracle?/ (14)

(14) C.K. Norwid, " Improwizacja

na zapytane o wieści z Warszawy”,

(1861) in Pisma wszystkie I, Wiersze I, Warszawa, 1971, p.383

Page 69 … the idea of

Polish-Jewish brotherhood. As the single most prominent episode in

current Polish-Jewish relations, it etched itself strongly in the

collective memory of the Poles. The Jewish presence in the

demonstrating Warsaw crowds not only gave the events a unique colour,

but also played a crucial role in creating the myth of the "people

of Warsaw". This new category born of the upheavals of 1861,

was seen as the collective incarnation of the national aspirations

of the Poles. The concept of "the people of Warsaw", a category

which included Jews and other strata of the urban population, was to

open a new chapter in Polish history. From the ideological point of

view the appearance of Norwid's rebellious "Warsaw child"

(====) pointed to important (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cyprian_Norwid)

changes in the Poles’ self-image as a nation. (The idea, and

manifestations, of the Polish-Jewish “brotherhood “ did survive only

for a few years!)

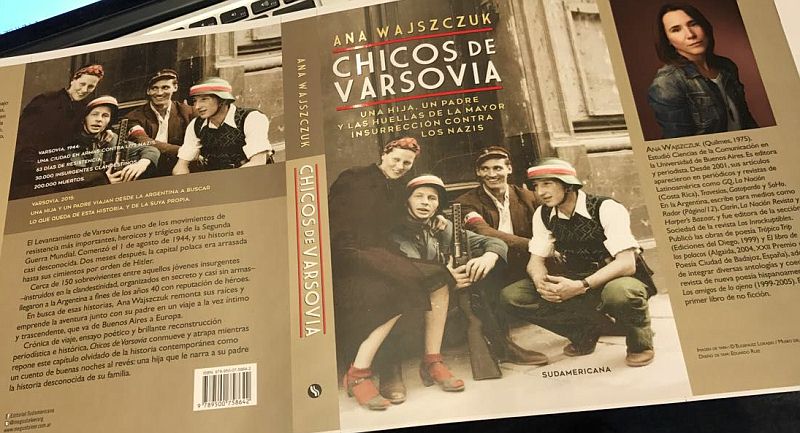

CHICOS DE VARSOVIA / WARSAW’S CHILDREN

A daughter, a father - in the footsteps of

the greatest insurrection against the Nazis

By Ana Wajszczuk

The cover of the book

This is the story of the Warsaw

Uprising as well as the story of my family: the Wajszczuks. A

real-life narrative where voices of the Uprising survivors who

emigrated to Argentina and still live at present – or their

children’s voices retelling those stories - melt together with

my personal history and the search of my own origins.

As a nonfiction novel, this book

intends through different voices to rescue the everyday life

history which happened during the Warsaw Uprising, narrated from

the journey to Poland I shared with my father in 2015 while the

71st anniversary celebration of that event was taking place.

This is an episode that, – despite being the bravest, most

important and tragic resistance movement of the Second World War

– is virtually unknown to the general public or mistaken for the

Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Upon the destruction of the city and the

death of two hundred thousand Warsovians throughout 63 days of

battle, nearly 150 Armia Krajowa (AK, the “National Army” or

“Patriotic Army”) veterans arrived in Argentina by the end of

the 1940’s. The purpose of this book is to raise visibility to

some of these stories which were never told before.

The book tells the story of Jorge Łagocki, who was a child when

the Uprising broke out (and through his testimony also come out

stories of civilians); of Hanna Baranowska, who took part in a

battalion (and shared stories of women belonging to the AK); of

Susana Grinspan and her father’s story about the Jews who

battled in the Uprising. Furthermore, Juan Ricardo and Jorge

Białous also reveal their father’s story – a famous scoutmaster

captain and the highest-ranking insurgent who came to Argentina.

95-year-old Feliks Lech recalls what it was like being part of

another battalion hemmed into the south of Warsaw, and Andrés

Chowanczak recounts his father’s experiences in that same

battalion.

There is a connection between these stories of insurgents who

came to Argentina and a branch of my family: four siblings,

residents in Warsaw – cousins of my grandfather, Zbigniew

Wajszczuk, who at that time served in battle for Commander

Anders’s Second Corps Polish Army in the East - fought during

those days. Danuta, the oldest sister, was the only survivor

among them. She continued living in Poland and died in the 70’s.

In Warsaw, under the guidance of one of my uncles who lives in

the United States and who has made an extraordinary work of

reconstruction of our family history (available in

www.wajszczuk.pl), my father and I interviewed relatives,

friends and acquaintances of the Wajszczuk family, in an attempt

to put the pieces together of the story of those siblings who

died in battle for Poland: 20-year-old Antoni, 18-year-old

Barbara, and 15-year-old Wojtek.

Historical research is sustained

by diverse sources: books such as Warsaw1944 by Norman Davies as

well as General Komorowski’s memories and the latest works by

English researcher Alexandra Richie have been really helpful.

Other testimonies and material from investigative journalism,

documentaries and films from my previous visits to Poland in

2008 and 2009 are also included.

This book is a chronicle and an

investigative journalism work, while at the same time narrates

the story of a father-and-daughter journey. It is an expedition

to find out who we really are and the comeback to our origins; a

narrative of immigrant origins that most Argentinians take

within us, and the story told from a daughter to her father –

like a bedtime tale- about the Polish family he did not know.

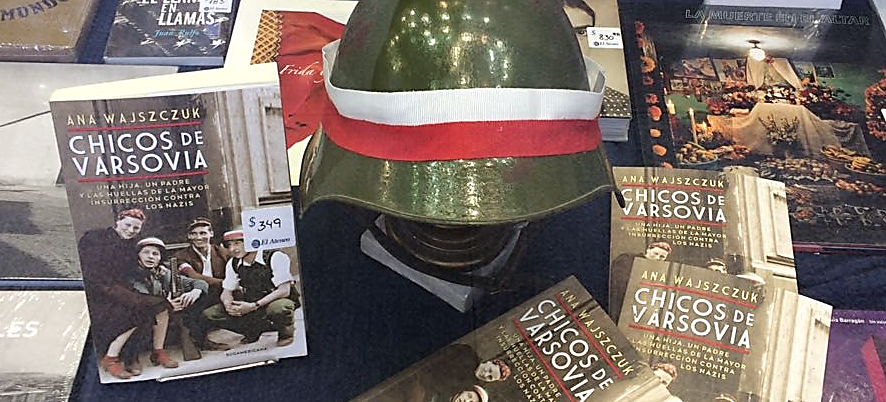

The book on display in a bookstore window in Buenos Aires, Argentina

CHAPTERS

Introduction. Opening scene:

a German (miniature) battle tank captured by the insurgents. The

tank blows up amid sounds of jubilation and laughter. Barbara

Wajszczuk gets injured.

Chapter 1. There is a city, where time stops for a minute every

year. My father and I in Warsaw. It is August 1st, 2015 and

celebrations to commemorate the beginning of the Uprising

overflow the city. What are we doing there?

Chapter 2. August 1st, 1944, 17:00. Beginning of the Uprising.

Introduction to the history of the Wajszczuk siblings, members

of the AK, the clandestine resistance against the Nazi

occupation.

Chapter 3. Siedlce Boys. How this story came to me. The email of

uncle Waldemar about our family tree which unveils an unknown

story in our family. My grandparents and the origins of the

family in Poland.

Chapter 4. Krochmalna Street. First days of the Uprising: Wola

massacre, Jorge Łagocki’s story –a 7-year-old boy at that time,

who spend the entire Uprising hiding in a basement- and how the

civilians lived during the first days of euphoria.

Chapter 5. Antoni, Basia and Wojtek. The death of the Wajszczuk

siblings on the first days of the Uprising: our visit to the

cemetery and their graves. Antoni – there is not much

information about him; Wojtek - homage and mass at Pęcice town’s

memorial site. We are hindered by “J” – Danuta’s son (Danuta was

oldest sister of the three siblings who died in the Uprising) -

to ask us to leave his family alone because he does not agree on

the publication of this book.

Chapter 6. Warsaw Girls. The story of Hanna Baranowska, the last

warrior alive in Buenos Aires. The role of women in the AK:

messengers, nurses, liaisons.

Chapter 7. Siedlce-Krasnystaw-Lublin. Journey to Siedlce, the

cradle of the family. I begin to feel disappointed, as no one

knows much and everybody says my next interviewee will surely

know more. Some traces about uncle Karol, who died in Dachau.

Visit to Majdanek. Aunt Lilka and the homage to the insurgents

of the family in the town of Krasnystaw. A visit to the family

graves with my grandmother’s ashes.

Chapter 8. Surviving Twice. Susana Grinspan, of Jewish origins,

tells me the story of her father, who managed to ran away from

the Ghetto and subsequently battled in the Uprising. Tension

between the AK and the Jews: the complex relationship between

Polish Jews and Catholics before, during and after the war.

Chapter 9. Basia: sharing reflections through the hospital

window. August 13th, 1944: Barbara Wajszczuk’s story - injured

by the explosion of a miniature German battle tank-trap, which

the insurgents unknowingly snuck in, like a “Trojan horse”. Dead

two weeks later when the hospital where she was recovering was

bombarded. In Warsaw we attend the homage to commemorate the

victims of that day. An interview with Antoni Dobraczyński ,a

blind, almost deaf man and the little pieces we managed to

understand from his story: he was the last one who saw her

alive. Other testimonies about what happened.

Chapter 10. Captain Jerzy.

Journey to Neuquén (Argentine

Patagonia) with my father to interview Jorge and Juan Ricardo

Białous, Captain Jerzy’s sons. Captain Jerzy was one of the

heroes of the Uprising, who was exiled to Argentina, on the

Andean foothills, 300km away from Neuquén. The Uprising is being

hemmed in. ???

Chapter 11. Mokotów Soldiers. End of the game. The last days of

the Uprising. The story of Stanisław Chowańczak told by his son,

and of Feliks Lech (who died shortly after I interviewed him),

both of them soldiers of the Mokotów district, the last area

which surrendered. The capitulation and Warsaw in ruins. Current

debates on the Uprising. My efforts to make sense of it all,

between some kind of overwhelming emotional attachment to their

heroism and critical views. How can a person understand a story

so distant in time and language?

Chapter 12. Warsaw passed through here.

Maria and Danuta (mother

and oldest sister respectively of the Wajszczuk siblings who

died in the Uprising): what became of them? How did they escape

from Warsaw? How did they hear of the death of the brothers?

Correspondence with uncle Waldemar. Pruszków Transit Camp for

civilians: a visit with my father. The camp’s inscription

“Warsaw passed through here”: more than 600 thousand people

walked through this camp, destined to slave labor in the Reich,

concentration camps and deportation to inland Poland. Oberlangen

Camp for female prisoners of war: final part to the story of

insurgent Hanna. Epilogue of the journey and the book: our last

day in Warsaw.

Praises for the book Chicos de Varsovia / Children of Warsaw in

Argentina:

“Ana Wajszczuk is living a personal spring. Her brilliant

historical memory Chicos de Varsovia (Sudamericana) is now in

its third edition. It is a moving story, which clears a path

between the course of WWII and the history of Polish resistance.

This is a book where the author gets the pieces of her family

tree, put them together and makes them flourish by dint of

asking, searching, digging in family histories.”

(Susana Reinoso, Clarín newspaper)

"The family research and the tragic history of the Polish

insurgence against the Nazi occupation perfectly matched with

prodigal harmony in Chicos de Varsovia, A great chronicle

written by Ana Wajszczuk"

(Alejandro Caravario, Brando magazine)

"Chicos de Varsovia (Sudamericana) is a multi-faceted, beautiful

and heart-breaking book which reconstructs the Warsaw Uprising

that began on August 1st 1944, a movement of resistance against

the Nazis which lasted 63 days and mobilized 30,000 clandestine

insurgents”

(Silvina Friera, Pagina/12 newspaper)

"As a writer and researcher, but also as the granddaughter of an

insurgent, Wajszczuk reveals to us the extent to which crimes

against humanity are, above all, a grievance to the future"

(Damian Tullio, Rolling Stone magazine)

"Chicos de Varsovia (Sudamericana) is one of the greatest books

of the year. The texts is a reconstruction of many heroic deeds,

but goes further and proves to be a learning novel. As the

author moves forward in the historical events, she veers off to

wonder about her place in the story, her relationship with the

family that remained in Europe and with her father, as well as

her struggle to embrace the unattainable past"

(Patricio Zunini, Infobae online newspaper)

"Through her book -which is a travel novel, and essay and

historical and journalistic investigation simultaneously- the

journalist and writer rescues a forgotten chapter of the Polish

history and dives into her own family history. And moreover: she

creates memory"

(Agustina Rabaini, Sophia magazine).

"Wajszczuk set out on a journey through time, space and language

to come close to a story that was partly of her own but also was

slipping permanently through her fingers. Wajszczuk explored it

all in full detail, with thorough examination and pliant eyes.

There are books quoted, heartbreaking testimonies, specialists,

museums packed with memorabilia and a city rebuilt after its

ruins. But the limits of the historical reconstruction –all that

we will never know- is also present in this investigation"

(Natali Schejtman, Radar, cultural issue from Pagina/12

newspaper).

"The first nonfiction book by the editor and journalist born in

Quilmes in 1975 is the promising surprise of the year. In a

mixture of genres which includes the travel chronicle, the

historical reconstruction and the poetic impulse, the author

tells her father his family history during the Warsaw Uprising

which took place in 1944."

(Daniel Gigena, La Nación newspaper)

Author’s Bio

Ana Wajszczuk was born in Quilmes in 1975. She studied

Communication Studies in the University of Buenos Aires and

works as an editor and journalist. Since 2001, her articles have

appeared in Latin-American newspapers and magazines such as GQ,

La Nación (Costa Rica), Travesías, Gatopardo and SoHo. In

Argentina, she writes for media such as Radar (Página/12),

Clarín, La Nación Revista, Sophia and Harper´s Bazaar. She was

the editor of the section Sociedad of Los Inrockuptibles

magazine. Furthermore, she is the author of the poetry books

Trópico Trip (Ediciones del Diego, 1999) y El libro de los

polacos [The book of the Polish] (Algaida, 2004, XXII Premio de

Poesía Ciudad de Badajoz, España). She also wrote poems and

short stories which are part of several anthologies and

collaborated as an editor for the magazine of new Latin American

poetry Los Amigos de lo Ajeno [The pilferers] (1999-2005). This

is her first nonfiction book.

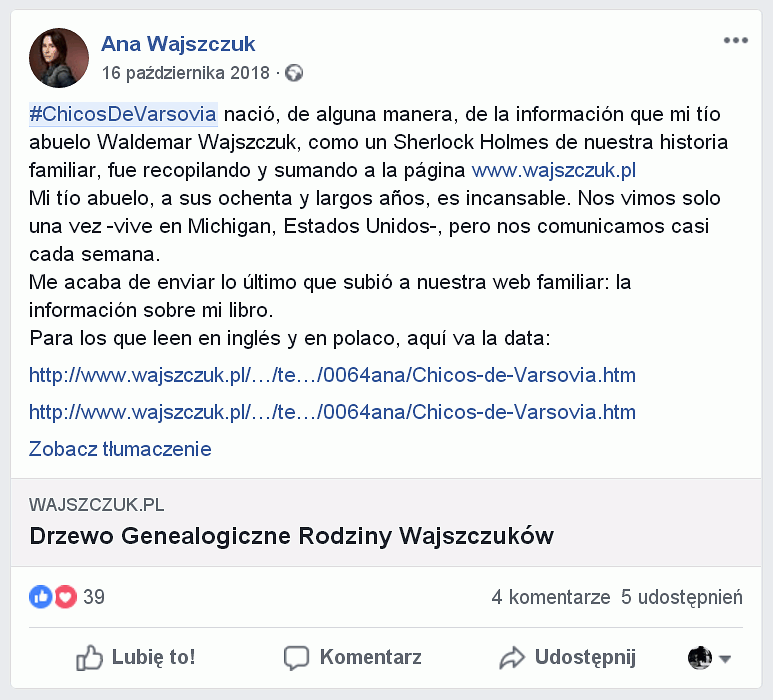

https://www.facebook.com/anawajszczuk/posts/2221357494766458

Translation

|

#Chicosdevarsovia was born, somehow, of the

information that my paternal grandfather’s cousin,

Waldemar Wajszczuk, as a Sherlock Holmes of our family

history, was collecting and adding to the page

www.wajszczuk.pl.

Waldemar, at his eighty and some years, is tireless. We

met only once - he lives in Michigan, United States -

but we communicate almost every week.

He just sent me the last item that was uploaded to our

family website: the information about my book.

For those who read in English and/or Polish, here is the

information:

//www.wajszczuk.pl/english/drzewo/tekst/0064ana/Chicos-de-Varsovia.htm;

https://www.wajszczuk.pl |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|